The Four Givens of Existence: Death, Freedom, Isolation, and Meaninglessness

Say it with me, now: death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness. Just reading the roster of these four metaphysical bogeymen hits you in the gut with a gulping thump of recognition. Known as “the Four Givens” in existential psychotherapy, together they form a simple yet provocative framework for reflection. These four words guide a person to lock in cognitively and emotionally to what existential inquiry is all about.

The Four Givens were first popularized by Irvin Yalom, one of the grandmasters of existential therapy, and a prolific author of both fiction and nonfiction works. When it comes to existential therapy he did, in fact, write the book. His epic work Existential Psychotherapy was published in 1980 and has been beloved by practitioners and grad school curriculum planners ever since.

Yalom described these four horsemen of existential work as the “ultimate concerns” of human beings, that are “given” in the sense of being inescapable parameters of our existence. There is no getting away from death, of course. We are all “condemned to be free” as Sartre said, whether we like it or not. There is some part of us that always exists in isolation, however rich our relational ecosystem. And finally, we are forced to confront a cosmos that is without any clear inherent meaning.

Despite the shock treatment of this litany, some deep down part of me exhales when I read it. As Yalom himself says, “However grim these givens may seem, they contain the seeds of wisdom and redemption.” What we can put into words, we can understand, and what we understand, we can find some kind of peace with.

Death

Death is the the host of this party, and us guests all have one eye on the door to see when he will make an entrance. Yet although death is ever-present in life, modern American culture has gotten very clever at suppressing our awareness of it. We only hear about it, we never see it. Even then it’s considered best to change the subject quickly. Only a century ago almost everyone died in their own homes with the whole household to bear witness, while today it is the exception for someone to die outside of a medical facility.

We feel the profundity of death only when it takes someone who we feel the absence of in a visceral, day-to-day sense. How calamitously confusing to body and mind that a person can simply stop being. We think we should call or text them before remembering with a jolt that there is nobody on the other end of the phone anymore. And of course, seeing someone else’s life simply stop reminds us that we, too, will someday cease to be.

An bizarre and appropriately unsettling publicity photo of Ernest Becker and his ole pal Death.

In his Pulitzer-prize winning work The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker asserts that much of human culture is an effort to symbolically outwit the all-erasing reality of death. This is made manifest in our efforts to leave a mark upon the world, what Becker calls our “immortality projects,” such as having children, creating art, forming organizations, and pretty much everything else. Becker’s ideas were later consolidated into “terror management theory”, which sees all these strivings as essentially different ways to subvert our terror at our own eventual annihilation.

A jolt of awareness of one’s own mortality can usher in an era of more vitality than ever before. As Yalom says, “Although the physicality of death destroys man, the idea of death saves him.” Many people I’ve known professionally and personally have become more committed to living their lives to the fullest only after losing someone or having their own brush with death. Experiences like that remind us that there really is only so much time and no guarantees to that, either.

In 17th century Europe a genre of art known as memento mori (“remember you must die”) rose to popularity. Works in this style commonly incorporate contrasting symbols of death and life (such as skulls and flowers) as a reminder to viewers of the transiency of life. Vanitas Still Life by Pieter Claesz, 1625.

Freedom

In recent blogs I’ve written a lot about Jean-Paul Sartre’s ideas about freedom. According to Sartre, because we are free we must confront and take responsibility for the choices that we make. While freedom has positive connotations in our culture, Sartre believed that most people are actually terrified of the open plain of freedom and as a result engage in a variety of evasive tactics to keep from seeing how much choice and responsibility they really have. A few of these are blame (“I can’t do anything different, my wife/husband won’t let me”), conformity (“It’s what you’re supposed to do”), and something Sartre calls “bad faith” which is pretending to ourselves that we are the role we are playing, rather than a human who is always making choices.

In my practice I work with a lot of young people newly encountering their freedom. This often looks like anxiety about the future and how to make choices about their life. Sometimes they are anticipating graduation, choosing a major, or realizing that their new career is not a good fit. It is striking to look in the eyes of a young person and realize they are making the biggest choice they have ever had to make, and they are terrified of doing it wrong.

One of my favorite literary passages about the pain and fear around choice in young adulthood comes from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. The main character imagines all her possible futures as figs hanging from a tree, of which she can only pick one, and finds herself so paralyzed by the choice that she is in danger of letting them all pass her by. Link to original artist’s webpage.

When we are growing up we become used to being the one with less information about the world than the adults around us. We learn to assume that someone older and wiser probably knows better than us. As we grow into adulthood our task is to eventually unlearn this habit of glancing to someone else to tell us the answer. Maturity teaches that while others might have helpful information, many choices are a balance of personal needs, inclinations, and contextual demands that are impossible for others to have the same sense of that we ourselves do. We evade our own responsibility when we give too much power over our choices to others.

In all fairness, learning what you yourself want is a difficult business. I often encourage my clients to turn inward and learn about their values in these cases. Choices are sometimes difficult because we have many values that are sometimes set at odds with one another. If we can name the competing values, it gives us the opportunity to look at our motivations more clearly, to compare and weigh them, and perhaps identify some middle ground that acknowledges multiple values. It is also helpful to integrate a somatic element: when you imagine yourself pursuing each option, does it make you feel excited and energized, or dull and exhausted?

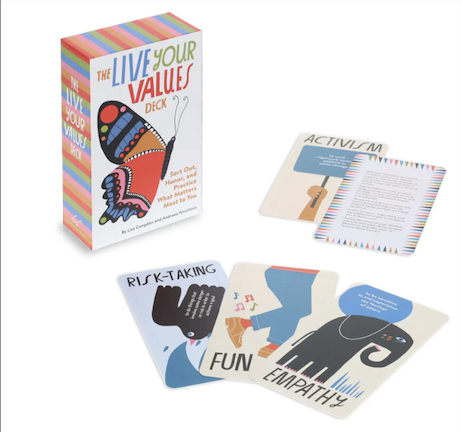

One tool that can help you hone in on your values is a card deck like this one by Lisa Congdon. I sometimes use these with clients to provide a visual aid in identifying, prioritizing, and committing to act on values.

Isolation

Existential isolation refers to the fact that no matter how rich our relational life, we are each alone in our experience as an individual organism. As we each have our own memories, perceptions, and mental life, the skin of our bodies constitutes an impermeable barrier between ourselves and everyone else. Yalom differentiates existential isolation from interpersonal isolation, which is the experience of being isolated from other people; as well as intrapersonal isolation, which is the experience of being disconnected from one’s own self. While these two forms of separateness might prime the exploration of existential isolation, it is also important to deal with them as their own issues.

Many of my clients deal with deep interpersonal loneliness. Austin in the 2020s is a modern boomtown, where people blow in and out on the winds of tech hiring cycles and academic admissions. It is difficult to establish roots in such loose soil. This of course is situated in the US, a culture whose social connectivity is declining at such an alarming rate that our Surgeon General has declared it a public health crisis. From the perspective of a therapist, chronic interpersonal loneliness is even more dangerous when it starts to feel permanent, factual, and personal to us and our unworthiness. (Link to my past post “How To Un-Lonely”)

Do we really want/need more than “this provincial life”?

Today’s problems are yesterday’s solutions, as the saying goes. In our ancestors’ villages one’s personal identity was reinforced as a fixed entity by dense webs of interpersonal knowledge and expectation (Link to my past post about the related concept of facticity.) How much a person might have dreamed for their own space to be and to grow! How magical it would seem, to have agency about whether to allow others into one’s energetic sphere! How hard it would be for someone dreaming the dream of our world, with big houses far apart, to fathom what they would lose.

Connecting with oneself, ie dealing with the intrapersonal form of loneliness is also crucial to approach more clearly the reality of existential isolation. Some of my clients struggle to tolerate their time alone, and their task is to cultivate this intrapersonal relationship. Connecting with oneself is a process that I describe further in this blog post. Like a re-spawn point in a video game, we are inevitably thrown back to ourselves. We can treat this internal home base like a crash pad with a mattress on the floor, or we can take the time to make it homey, put some art on the walls, brew up a cup of tea.

This is the vibe I’m talking about. Illustration credit Jill Barklem, Winter Story.

We might just find that if our interpersonal and intrapersonal needs for connection are met, and if we work through some of the reflexive anxiety, that it is not such a bad thing to be our own self. Perhaps a more neutral to positive wording for existential isolation could be “existential uniqueness.” If we can cultivate comfort with being an individual having our own unique experience, we might even find that we are able to participate more honestly and openly in relationships and with more bravery and honesty in our day-to-day lives because of it.

Meaninglessness

While relevant to all of us, questions about meaning show up most intensely with my clients who are experiencing some kind of unrelenting suffering. This often involves depression, although the depression itself might be related to another issue, such as chronic illness or an addiction. If the cost of living each day feels painfully high, then a person starts to wonder if they are making a bad bargain.

An indifferent universe, like a neutral facial expression, has a very different meaning depending on one’s emotional state. When emotional seas are more placid we may still be drawn to explore meaning, but we may not mind so much that our lives do not matter on a grand scale. Sure, I might be cosmically insignificant, but I can still find it satisfying to enjoy a banquet of things meaningful to me within the scale of my own life.

My clients sometimes come in thinking they need to find a single monolithic meaning to their life, but the truth is most of us find it by assembling a collection of things (relationships, experiences, projects, etc.) that we personally find beautiful or compelling; like these found object mosaics by artist Jill Gatwood.

Once in a misguided attempt to communicate this to a depressed client, I quoted Camus’s description of “the benign indifference of the universe.” My client shot back a quote from Stanley Kubrick about “the terrifying indifference of the universe.” Touché. If someone is depressed with themes of meaninglessness they must not ignore the biopsychosocial basis of depression, so it remains crucial to do the things that help depression (therapy, self-care, medication in some cases.)

Our tragic flaw as a species is also one of our most remarkable strengths, our obsessive talent for seeking and identifying patterns. This tension between the innate human drive for meaning and the apparent meaninglessness of the universe is known in philosophy as “the absurd.” While we might use this word in daily parlance to describe something that is generally ridiculous or silly, in the philosophical tradition it specifically describes this existential boondoggle. Humans want meaning. The universe offers none. And yet we seem functionally unable to stop permuting new possibilities of what meaning might be, or could be, or should be, on both a global scale and within our own individual lives.

Thank you Existential Comics for this most excellent interpretation of “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Albert Camus is the philosopher most closely associated with absurdity. In his classic essay the Myth of Sisyphus he uses the Greek myth of Sisyphus as an allegory for absurdity. Because he offended the gods, Sisyphus was tasked for all eternity to push a boulder up to the top of a hill, only to have it roll down to the base of the hill every time. When this happens he must push it up again. Forever.

But as Camus states, “There is no fate that can not be surmounted by scorn.” Camus’ conclusion of this essay is “One must imagine Sisyphus happy”, ie that despite the window dressing, our own situation is not so different. We must be able to believe that even if there is no clear point to life, if we choose to live the endeavor is still a worthy one that we can nonetheless take joy and pride in because it is our own.

Conclusion

These givens are not a life sentence to suffer, they are a formula to learn from. Precisely because we cannot escape them our only meaningful course of action is to reconcile with them, and this reconciliation opens up the opportunity for a personal response. We have a chance at “redemption”, as Yalom puts it, by way of our responsibility to and honesty with ourselves.

In fact each of these givens implies a particular response. With an awareness of death, we are spurred to more committed living in the span we have. With freedom, we are urged to take responsibility for what we make of this time. Isolation reminds us of the necessity to connect with other beings, however imperfectly, as well as ourselves. And a lack of preordained meaning liberates us to pursue what we feel to be personally meaningful. Like the constraints of any artform, these Four Givens shape the artistry we must conjure in living our own singular precious life.