Being Seen As a Basic Need

It is existential oxygen to feel seen by another human being. And like oxygen we know it most clearly in its absence. As we trundle through our day-to-day we don’t necessarily expect or want deep connection at every turn, but even the most introverted of us must refill our cup somewhere, sometime. When we do finally make contact with our friend, our partner, our therapist, our people who get us, we allow our tender essential squishy bits to come out, shyly or with the gusto of great heaving relief.

In the last year, I’ve had more clients than ever bring up “not being seen” as one of their core struggles. For these individuals, to be omitted from social reality feels like losing one’s reality altogether. The gaze of another person flicking past, or even a polite mask of a smile, cements the feeling of being irrelevant. Perhaps we can hold onto our value in our own hearts despite these slings and arrows, but most of us can only take so many hits. The undercutting of value impacts a person deeply, sometimes to the point of causing wholesale withdrawal, especially if there is a history of relational neglect, abandonment, or rejection.

When we feel seen, we know that another person understands us and values us in a single moment, and through that moment, seems to understand and value us in our totality. We develop the capacity of feeling seen in our early childhood with the people closest to us. The mutual gaze of the parent and child is the ur-image of this need being met. Throughout our lifetime, making and keeping prolonged eye contact with another is linked to oxytocin release, bonding, and feelings of intimacy and closeness.

It’s not just about whether someone looks at you or not, of course. At the extreme end of not being seen is the tragedy of neglect, where a child’s basic and emotional needs go unmet. But it doesn’t need to be this extreme to leave a vacuum. For many people who grew up in households that cared for them, even loved them, it is still apparent that their caregivers still never quite brought them into focus. These omissions during critical periods of development may confer an especial sensitivity to not being seen later in life.

The performance artist Marina Abramovic famously explored the experience of mutual gaze in her marathon performance piece The Artist Is Present, performed in 2010 at the Museum of Modern Art. For the work she invited strangers to sit opposite her, one-at-a-time, without speaking, over the course of several weeks. More than 1500 people accepted the invitation, including celebrities such as James Franco, Björk, Lou Reed, and Alan Rickman.

This feeling of being chronically unseen can develop from present-day experiences in adulthood as well, either from a lack of relationships or a lack of depth in one’s relationships. We humans are social animals, and because of this it is not strange that we need to share ourselves and the experiences in our lives if they are to feel meaningful. My lonely clients sometimes reference the Zen koan, “if a tree falls in the forest with nobody to hear, does it make a sound?” The personal parallel of this being, “If I am alone in my apartment, do I really exist?”

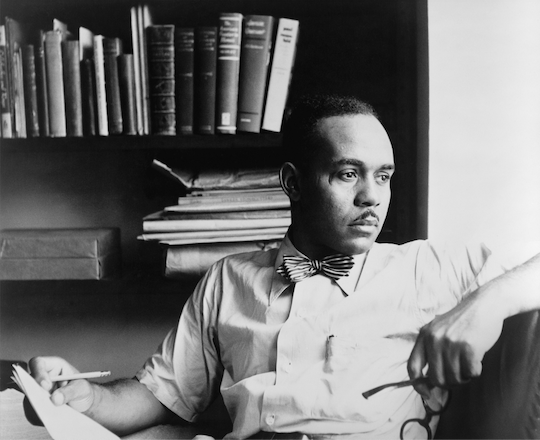

On a societal level, a person can feel unseen because their experience is on the whole discounted or ignored. Social psychology describes this phenomenon as “invisibility syndrome.” Frequently applied to race and in particular the African-American experience (especially in the work of psychologist A.J. Franklin), invisibility syndrome has pernicious and holistic effects on a person’s mental health and overall wellbeing. Literature offers us a haunting description of this experience in the opening salvo of Ralph Ellison’s 1947 novel Invisible Man:

“I am an invisible man. . . . I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.”

The author Ralph Ellison.

While African-Americans are profoundly impacted by invisibility syndrome, other demographics such as women, people with disabilities, and members of the LGBTQ+ community suffer from this as well. In fact, there is no group (yes, even cisgenderd heterosexual White men) that does not suffer sometimes from having the autocomplete-esque assumptions of others take away their individuality.

When we feel unseen, seeing ourselves may be crucial as a starting point. To do so, the author and philosopher Viktor Frankl describes a pivotal prerequisite step of “self-distancing.” Frankl’s protege Alfried Laengle further refined the idea in his psychotherapeutic method of Existential Analysis, which looks at mental health issues through the lens of existential needs. In Laengle’s words, to self-distance is “to step into a distance from oneself from which one can freely deal with oneself.”

For more about this concept check out my previous blog post on the topic.

In essence, this move demands that we disentangle the multiplicity of selves that we are for just a moment in order to make choices that align with our values. We tease out an observing self as well as the one that is experiencing something immediately, perhaps having a strong emotion or making a difficult decision. Just as we cannot see the details of something if it is pressed against our face, we need to hold our own selves out at arm’s length in order to better see and appreciate them. Through this we can gain perspective where before was only confusion.

The most basic way of self-distancing is to deliberately script an internal dialogue with ourselves, allowing different parts of ourselves to take both sides of the conversation. Writing this down can help maintain the necessary self-distance, and avoid getting sucked into unhelpful thoughts loops. Any creative act, especially when undertaken with an emphasis on process rather than product, can also help us to self-distance. This might be as prosaic as a LEGO sculpture or an off-the-cuff sketch while we wait for an appointment or entertain a child, but might be something slower and more intentional for a deeper experience.

Edward Hoppers’ Office In a Small City, 1953.

Seeing and taking oneself seriously is the prerequisite of forming a stable inner relationship, a concept that may seem strange and ineffable at first, but is fundamental to one’s wellbeing. When one’s relationships have atrophied, seeing and relating to oneself can be a stepping stone to build the strength and resilience to risk being seen by others. Therapy, of course, is another stepping stone that can help you practice seeing yourself and being seen by another who may be easier to tolerate, because you know the relationship is safe, protective, and has your own growth and wellbeing at its heart.

In an individualistic, hypermobile, and technology-saturated society, being seen has become a need that is both more critical and more scarce. Seeing and being seen is by nature a slow gaze, requiring a calm settled state antithetical to the activation and goal-directed nature of a life that is too fast-paced. To find it we must learn how to give it, both to ourselves and those around us. Resist the urge to keep going as fast as you always have, step outside the current, and take a deeper look.