Existential Guilt

My client pushes her hair back and smiles, but her body remain tense. “Whatever I’m doing, I’m always wondering if I should be doing something else.” Her leg is jiggling now. “Or I’m thinking about how fast I can finish and get to the next thing, like maybe I am picking wrong but I can still fix it by just, you know, doing everything.” I can tell by her voice and her face, it's exhausting her. She’s come up against the hard stop of her human limitations of time and capacity, and left to reckon with the prickling question “am I doing what I’m supposed to do in this life?” Existential philosophers call this phenomenon “existential guilt.”

Existential guilt is the feeling that arises from knowing that out of the multiverse of lives we could live, we have chosen–are, in fact, continuing to choose–this particular life. Because these alternative paths exclude one another, we hereby condemn to the cosmic dustbin all those other possible pathways, which still contain other valued actions and relationships. As we can see in the case of my client, it can be accompanied by fantasy, regret, anxiety, feelings of failure, and all-around metaphysical FOMO.

In fact, classic meme you cannot. (Credit for original image to Allie Brosh’s Hyperbole and a Half.)

Two thinkers in particular helped to define and describe existential guilt, although they arrived at somewhat different conclusions about it. In the 1920s, the German philosopher Martin Heidegger wrote of existential guilt as an inevitable and constantly present feature of human life. In his eyes, to be human means to be guilty (Have we heard this story before?) As we’ll explore below, several decades later the American psychologist Rollo May evolved Heidegger’s concept of existential guilt in a new and thought-provoking direction.

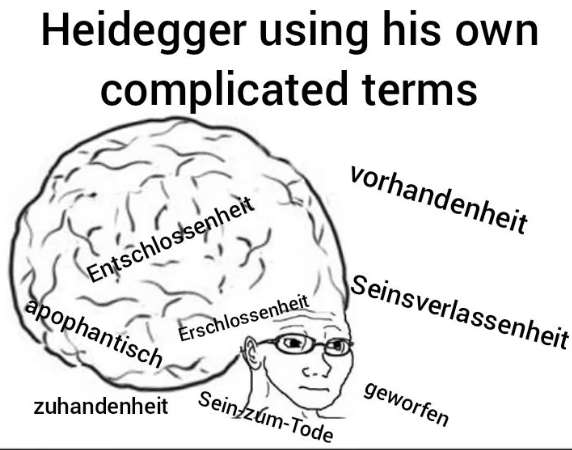

In order to understand Heidegger’s concept of existential guilt, it is helpful to become familiar with a few of his other terms. Heidegger’s writing is famously obtuse but also strangely poetic. Despite and even because of his work’s highly theoretical nature, he was committed to capturing the immediacy of human experience in his language. In order to do this he created new terms for common experiences that could conjure a fresh sense of encounter with the everyday.

Click here to be whisked away on a whirlwind tour of Heideggerian terminology!

In his classic work Being and Time, Heidegger proposed that human beings are unique creatures best defined by our existence in the field of time (hence the title) or as he calls it “temporality” or sometimes “historicity.” As far as we can tell, humans alone among the animals ponder our individual past, present, and future beyond mere survival. We are also “Beings-toward-death” in that we exist within a limited timespan, with the bookend of death as a defining characteristic that we are always moving towards. This inherent limitation and the fact that we cannot in fact do all the things is what defines us, because it forces us to make choices of how to spend our limited ticking clock’s worth of a life. Cheery stuff, eh?

Human life is also built on a fundamental “groundlessness” according to Heidegger and his philosophical predecessors which refers to the lack of predetermined meaning or values in life. Outside of religious systems and social contracts, there are no rules to the game, no win conditions, no losers in any absolute sense. We play for a while and then we are extinguished. We are the authors and the readers of the text we create, which is both freeing and fucking confusing.

Heidegger in his study. I dig the ivy.

Many people flee this morass by retreating into conformity as justification for their actions: “I do this because it is what other people around me do, and what is expected of me.” Heidegger described this as throwing oneself to das Mann, or in English, “the They.” Das Mann is the anonymous public, the amorphous rank and file in our head that enforces oughts and shoulds. In Heidegger’s view, to throw ourselves to their standards reflects fundamental inauthenticity and an unwillingness to face one’s own groundlessness and responsibility of choice.

Caught within groundlessness, we humans are always left wondering, “Am I doing it right?” If I successfully avoid letting das Mann steer my life, I am still faced with endless choices. If I choose to pursue my career, I may always wonder what it would have been like to invest in my artistic passion. If I choose to be a parent, I may not be able to travel as much as I would like. As my client expressed, this can happen in the more immediate choices of what to do in one’s day as well. Go to the party or get some restful time alone. Get the chicken or the steak. According to Heidegger and his characteristic severity, we are inevitably ensnared in a force field of guilt for all the valued things we have not done.

As the author of 19 books as well as numerous essays and articles, Rollo May deserves much of the credit for adapting existential philosophy into a modern American approach to psychotherapy.

Working in the heady foment of 1960s California, Rollo May’s work fused insights from Old World philosophy, psychoanalytic concepts, and his own personal experience. In particular, he adapted Heidegger’s concept of existential guilt into one that aligned more comfortably for modern Americans and our pull in the forward direction. After all, we Americans are and perhaps in that time were even more a people stereotyped by our (sometimes exasperating) optimism and orientation towards action, the roll-up-our-sleeves go-getters who want to know what to do about a problem.

While broadly accepting Heidegger’s concept existential guilt as always ebbing and flowing in our lives, May emphasized that when existential guilt becomes acute it reflects a diagnosable problem in that “the person denies [their] potentialities, fails to fulfill them.” When one feels this constant and rising pressure of extreme existential guilt, we must ask ourselves what it is trying to tell us. Often it means we are ignoring something that we know in our bones we were made to do or try, and we are doing so because we are afraid.

While best known for his writing on psychology and philosophy, May remained a staunch advocate of integrating creativity into one’s life as well. This is demonstrated in his book My Quest For Beauty which showcased many of his own paintings such as the one above.

Throughout his career, May championed the human capacity to understand and integrate feared existential such as this one, believing that confrontations such as this offered what his protege (and therapy client!) Irvin Yalom called “the seeds of redemption.” Or, as another of May’s influences Jean-Paul Sartre put it, “Life begins on the other side of despair.” According to May, intense existential guilt offers one the potential for a better life in our awareness and willingness to converse with it, with his declaration that it “can and should lead to humility…sharpened sensitivity in relationships with fellow men, and increased creativity in the use of one’s own potentialities.”

If we return to the client at the beginning of this post, we can imagine her talking through this guilt and all it might be able to illuminate. Perhaps some of the things she imagines doing scare her. Perhaps some of them exert an irresistible pull. In time she may be able to identify which of the things not done and roads not traveled remain most persistent, and she determine whether there is something that feels important enough to her life to pursue despite the uncertainties and the sacrifices of other paths. The quintessential thought experiment here is, when you are on your deathbed, what do you not want to regret?

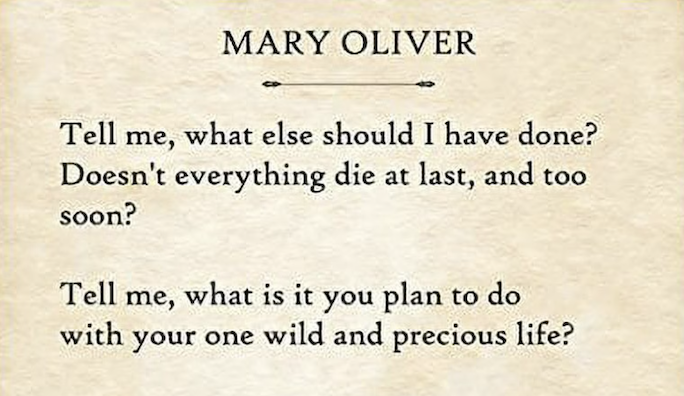

In her classic poem “The Summer Day”, Mary Oliver asks us this most poignant of questions.

One concrete activity we can turn to in order to help review priorities and deal with existential guilt feelings is the examination of values. Values identification and activation to deal with transitions, anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues is integrated into many forms of existential therapy, most prominently in the behavioral but existentially inspired approach of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. In ACT, clients are often asked to identify their values (sometimes using a list like the one linked to below to aid them, although using your own terms is fine too) in order to concretely prioritize what is most important to them.

This activity may not speak to everyone, but for some of us naming priorities can create an island of solidity in the primordial goop of groundlessness and possibility. When working with clients, I recommend choosing three to focus on as a present personal mission statement, with a key word being “present” because, of course, priorities change. There may be many more than three that speak to you, but part of choosing is committing. Knowing your identified values can help give some guidance to the endless decisions about both the everyday and the large-as-life. If authenticity is important to me in this season of my life, perhaps I won’t go to that party when I’m feeling low-energy. On the other hand, if adventure is the value I chose out of the line-up, perhaps I will. For more on values identification exercises, check out xyz

The combined work of Martin Heidegger and Rollo May illuminate how we can understand and respond to existential guilt. While Heidegger’s work provides the phenomenological framework, May’s work gives us the map forward in his encouragement to treat existential guilt like any other emotion: a signal that something needs to be reexamined. Only after we face our own existential guilt and its elements of groundlessness, Being-Towards-Death, and fundamental responsibility can we answer the call to live our own unique and authentic expression of a life.

Lots of inspiration was drawn from the following article:

The Call of the Unlived Life, by Per-Einar Binder.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9557285/